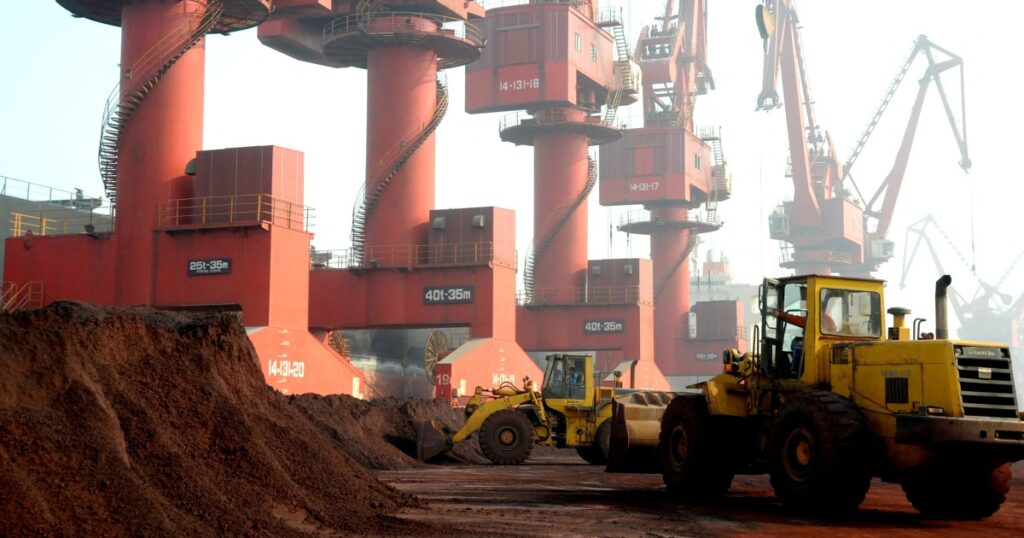

As China threatens to limit supplies of rare earths, the United States and other countries dependent on critical minerals are scrambling to diversify their supply chains and achieve self-sufficiency.

But even with sustained political will and billions of dollars in investment, it will likely take at least a decade, if not longer, to break China’s grip on rare earth supplies, analysts and industry experts say.

Recommended stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

For countries to reduce their dependence on China, they need to secure complex supply chains spanning mining, processing, metallization and magnet manufacturing.

Promoting self-sufficiency faces challenges such as high capital costs, gaps in technological expertise, and environmental risks.

It also includes tracking moving targets, as demand for minerals used in everything from smartphones to electric cars to fighter jets is surging.

Ryan Castilleux, founder and managing director of Adamas Intelligence, said that with “sustained policy and investment momentum,” it will likely take 10 to 15 years for the U.S. and its allies to build supply chains with the “breadth and depth” to support growing demand.

“The United States currently imports about 10,000 tonnes of rare earth magnets from China annually, and Europe imports more than 25,000 tonnes,” Castilleux told Al Jazeera.

“In both regions, the demand for magnets is growing significantly. This number will increase many times over the next 10 years.”

President Donald Trump’s administration has taken a flurry of actions to boost access to rare earths, including stockpiling supplies, fast-tracking new mining projects in the United States and acquiring stakes in two Canadian mining companies.

Trump has also shown goodwill to foreign governments.

Last month, his administration oversaw the signing of an agreement between Missouri-based U.S. Strategic Metals Corp. and Pakistan’s military’s Frontier Works Organization for exports of the South Asian country’s minerals.

In April, Washington reached an agreement with Ukraine, under which Kiev agreed to share in the profits of future product sales.

On Monday, in the latest step to strengthen supply chains, President Trump and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese signed an agreement to invest billions of dollars in rare earth projects in Australia.

Under the latest agreement, worth a total of $8.5 billion, the Australian and US governments will be able to take ownership of the project, which guarantees the supply of critical minerals including terbium, yttrium, holmium and erbium.

Although it holds significant reserves of important minerals, Australia is unlikely to replace China on its own. The country’s reserves are only about one-seventh those of China, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Shares of rare earth companies soared Monday, with Oklahoma-based mining and processing company USA Rare Earths up about 14%.

Similar efforts to promote self-reliance are underway in Europe and Asia.

Under the Critical Materials Act adopted last year, the European Union has set ambitious targets to reduce mineral imports, including processing 40% of annual consumption within the region by 2030.

Europe’s first rare earth magnet facility opened in Narva, Estonia in September, a few months after the Solvay processing plant in La Rochelle, France, commissioned a new production line.

India and Japan, among other major Asian economies, are also moving to shore up domestic supplies and invest in projects outside China.

“Even if there is strong political will, we cannot move too quickly to permitting, financing and technology for these complex projects,” said Ross Chandler, a post-doctoral researcher at the Australian National University who studies critical minerals, describing efforts to reduce dependence on China as a “decade-long process”.

“China dominates midstream separation, refining and metal manufacturing, but not so much mining,” Chandler told Al Jazeera.

“Building expertise and capabilities elsewhere is technically complex, time-consuming, and capital-intensive.”

For the United States and its allies, the ability to process minerals is a more pressing concern than the amount of mineral deposits in the ground.

Rahman Dhyan, a senior lecturer in the School of Mineral and Energy Resources Engineering at the University of New South Wales, said these countries hold an estimated 35 to 40 per cent of the world’s reserves, but only about 10 to 15 per cent of refining and processing capacity.

“From 2030 onwards, if all the planned projects, recycling efforts and stockpiling strategies are successful, Western countries will be able to secure the bulk of the demand,” Dayan told Al Jazeera.

“While complete decoupling is complex and highly dependent on cost and market dynamics, Western countries can strengthen their position by sharing reserves, production capacity and competitiveness through a green premium.”

China has long had a monopoly on rare earth supplies, the result of a sustained state-led investment drive that analysts say has not been hampered by environmental and economic feasibility concerns that would affect similar projects in the West.

The country currently accounts for about 70% of mining operations and 90% of processing operations, according to the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“China has been investing in mining and mineral processing for decades and now controls raw ore, refining and downstream manufacturing,” Hayley Channer, a rare earths expert at the Center for American Studies at the University of Sydney, told Al Jazeera.

“This way, we have created an end-to-end supply chain.”

China’s stranglehold on mineral resources, which has been going on for decades, has taken on new urgency since China announced plans earlier this month to require foreign companies to obtain licenses to export Chinese rare earth equipment and materials.

Under export controls scheduled to go into effect on December 1, companies around the world will need permits to export rare earth magnets and certain semiconductor materials that contain even trace amounts of minerals produced in China or with Chinese technology.

The announcement is widely seen by analysts as an attempt to gain leverage in trade negotiations ahead of a meeting between President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping later this month, and has raised alarm among governments and businesses as disruption looms for global supply chains.

Adamus Intelligence’s Mr. Castilleux said that once the rule is fully implemented, existing export controls will look like a “minor inconvenience.”

“Existing supply chain issues, bottlenecks and assembly line disruptions will become more manifold,” he said.

Karem Kassim, an analyst at the Malaysian Institute of Strategic and International Studies, said he expected China’s dominance in the sector to continue “for at least a decade.”

“The biggest barrier here is not money, but time and sustained political will,” he told Al Jazeera.

But even if the United States and its allies reduce their dependence on China’s rare earths, Karem said the broader strategic rivalry with China is unlikely to abate.

“Reducing one dependency will not alleviate tensions. In fact, it may even shift the arena of competition to new sectors and value chains,” he said.