METEPEC, Mexico (AP) – Mexican artisan Hilario Hernández couldn’t believe his good fortune when he first met the Pope. He did not come to the Vatican as a guest, but as a guardian of the fragile pottery he had made as a gift. Benedict XVI.

“Nobody thought to take me,” Hernandez said. “But the Tree of Life breaks easily, so I took the opportunity to bring it myself.”

The work he was commissioned to create for the Pope in 2008 was mexican craftsmanship.

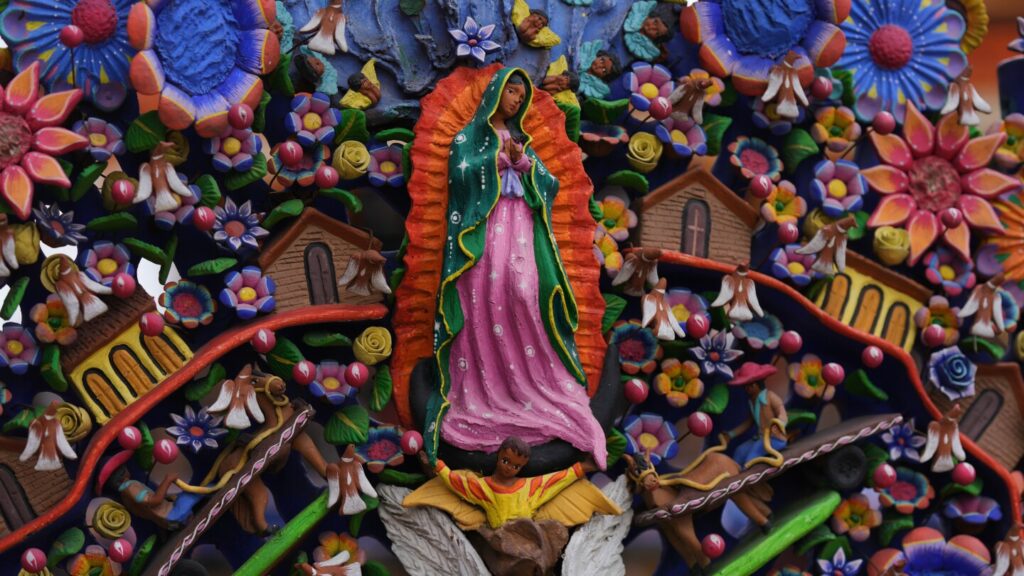

Known as the Tree of Life, it belongs to a tradition that flourished in the hands of artisans in the mid-20th century and is considered a symbol of identity in Hernández’s hometown.

In Metepec, where he lives and runs a family-run workshop about 65 kilometers southwest of Mexico City, dozens of artisans are dedicated to creating the Tree of Life. Their designs vary, but most share a common motif. It is a scene from the Bible’s Genesis, centered on Adam and Eve, separated by a tree trunk and a coiled serpent.

“With this wood, you can express whatever you want,” says Carolina Ramirez, a guide at the Metepec Clay Museum. “It’s a source of pride for us because it’s become part of the town’s identity and charm.”

The museum holds an annual contest, encouraging artisans from all over Mexico to submit their own versions of the tree. It currently houses more than 300 works, a selection of which are on permanent display.

In addition to Adam and Eve, trees also appear in many other ways. Katrinas — The skeletal female statue that became a symbol of Mexico day of the dead Celebration — and Xoloitzquintlesa hairless dog sacred to the ancient Nahua people.

“The wood theme comes from our culture and tradition,” Ramirez said. “And for the people who buy them, they have become a source of identity.”

clay heritage

Hernandez’s ancestors have been making clay objects for as long as he can remember. His grandfather, now 103 years old, continues to make pots in Metepec.

“We are the fifth generation of potters and artisans,” said Felipe, one of Hilario’s younger brothers. “Our knowledge is passed down by word of mouth.”

All five siblings trained for technical careers. None continued to practice it, choosing instead to become full-time artisans.

Hilario, the eldest, became the leader of the brothers. Their tasks now alternate between them. While one person is shaping the leaves, another person is adding the leaves and drawing pictures. All are proud of their family heritage.

Lewis, now 34, said he had been making Trees of Life since he was 12 and recalled, “This workshop was my playground.” “What I thought was a game at first turned into my job.”

Another local artisan, Cecilio Sánchez, inherited his father’s skills and established his own workshop. Now, his wife, two children and other relatives are working together to create their own tradition.

His technique is known as pigmented clay and consists of mixing clay and oxides. “Some of our fellow artisans add industrial pigments to their work, but our job is to preserve what the earth itself gives us,” he said.

Where tradition and mythology meet

While making his first tree for the Pope, Hilario pushed himself to the limit as a craftsman.

He drew on his father’s ancestral wisdom to fire the 2-meter-tall (6.6-foot-tall) piece of clay at just the right temperature. To transport it, he used 200 rolls of toilet paper to wrap it like a giant mummy, cushioning and sealing all cavities.

Then there was the design. For six months, he and his family patiently created the figures on both sides. This is a challenge that businesses rarely face. One face told the story of Mexico’s most revered saints. Another is the origin of Metepec’s Tree of Life.

The details of the circumstances are unknown. However, experts agree that such trees may have played a role in evangelization after the Spanish conquest in the 16th century.

Ramírez says the first artisans to reinterpret them into modern times incorporated elements unique to Metepec. One of them is known as Tranchana, a half-woman, half-serpent figure that, according to legend, once ruled the waters surrounding the town.

“It was believed that by coming out of the water, she brought abundance,” Ramirez said. “For our ancestors, the gods were associated with fire, water, and nature.”

However, the character of Tranchana in Hernández’s Tree of Life no longer resembles a snake. In the Catholic worldview, reptiles are seen as symbols of evil, temptation, and death, so their tails were replaced. Her current form as a mermaid is perhaps Metepec’s most iconic symbol, along with the Tree of Life.

faith in his hands

Hilario keeps a special frame on his workbench containing a photo of the day he met the pope for the second time.

At that time, he did not go to the Vatican. In 2015, a stranger knocked on his door and asked him to create another Tree of Life, this time for another Pope. Francisco was to visit Mexico soon, and the president wanted the artisan to present him with a masterpiece.

Hilario’s new role required three months of hard work from his family. Francis’ tree is not as tall as the tree made for Benedict. However, this design presented its own challenges as it depicts the life of the Pope.

The craftsman visited nearby chapels, talked with priests, and read as much as he could. When he met with the Pope inside Mexico’s presidential palace in February 2016, he realized that he still had much to learn.

“He ended up explaining his tree to me,” he said. “And he added, ‘I know you didn’t do this on your own, so God bless your family and your hands.'”

That encounter had a life-changing impact on him. It made him reflect on his purpose in life and reaffirm his commitment to his craft.

“Creating the Tree of Life is a commitment,” he said. “It’s how we make a living, but it’s also how we keep our culture alive.”

____

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through The Associated Press collaboration Funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. in collaboration with The Conversation US. The AP is solely responsible for this content.