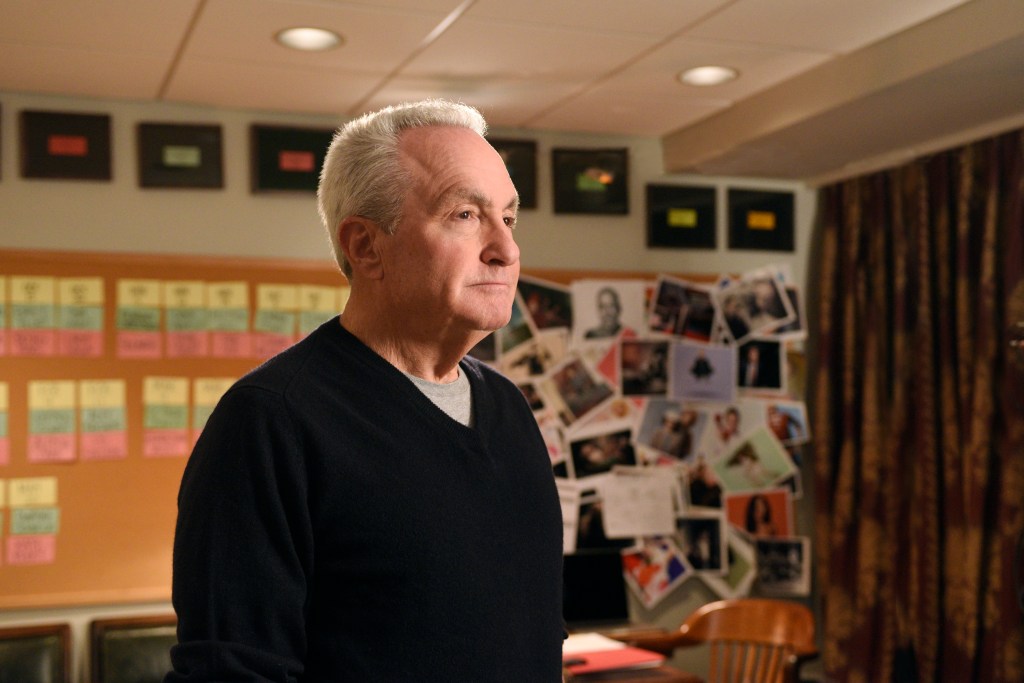

There has been “an air of kismet” about Susan Morrison‘s 10-years-in-the-making biography of Saturday Night Live creator and executive producer Lorne Michaels, the author said.

The New Yorker editor managed to penetrate the still-secretive process of making the show, weaving in-the-room reporting from a week when Jonah Hill hosted in 2017 with hundreds of interviews, including many hours with Michaels himself. “There were absolutely no conditions, no strings of any kind,” she told Deadline. “Nobody pulled anything back.”

The result of those efforts, Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live, was published this week by Random House, just two days after the 50th anniversary prime-time special aired on NBC. On nearly each of its 600 pages, the book sheds intriguing light on Michaels and his creation. It documents his winding journey to 30 Rock and revisits defining battles like an infamous showdown with NBC West Coast boss Don Ohlmeyer, who wanted Michaels to fire Chris Farley and Adam Sandler during a high point for the show in the 1990s. (If you think you already know how that went down, read the book.)

In an interview, Morrison shared her reaction to the prime-time special, which she watched from a New York hotel room with a handful of SNL writers she has long known. “I wouldn’t say anything surprised me about it, but it really did encapsulate what Lorne’s secret sauce is from the opening shot,” she said of the Paul Simon-Sabrina Carpenter duet. “They pulled it off. It was just beautiful.”

Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live’ by Susan Morrison

Taylor Jewell

The lack of dress rehearsal (an impossibility given the number of guest stars and the sprawl of three hours) meant that “the show got a tiny bit ragtag toward the end,” Morrison said. “Dress is when Lorne slices and dices and does his mad-scientist thing.”

As to the absence of political material, usually a staple of a regular episode, “in my frame of reference, I don’t think politics is that funny right now,” the author said. “A lot of people have said to me that this SNL [anniversary] came at the right time. It’s a diversion from the hell we’re living through.”

In her quest to bring readers a full portrait of the famously press-averse Michaels, Morrison had a few advantages. Very early in her career, she had been one of his assistants at SNL and formed relationships with many staffers that continue to this day. She noted that she wasn’t friends with Michaels and would “bump into him once a decade.” But her post as articles editor at The New Yorker and her longtime friendship with the magazine’s Lillian Ross and William Shawn (both heroes of Michaels’) also helped, as did her being in the audience as a teen-ager for an episode during the show’s first season.

Given the limitations of book publishing, the 50th season and the attendant speculation about the future of the show and its creator could not be included in Lorne. Asked about his next chapter and whether he will pass the baton to Tina Fey, Seth Meyers or Colin Jost, Morrison said all would be fine choices, but “I have a theory.” Much of the essence of the show “is his taste. So, it’s really hard to imagine him just stepping away from that.” One of Michaels’ oft-repeated sayings, which is cited in the book is, “You know when people leave show business? Never. No one ever leaves show business.”

Morrison said she expects a slimmed-down version of his current routine. “I could see a scenario that cuts way back on his time in studio,” she said. “Maybe he comes in Wednesday for read-through and the meeting where so many decisions are made about that week’s show … and then he could come in Saturday for dress rehearsal and all of the slicing and dicing.”

Regardless of the details of the final chapter for Michaels, who turned 80 last November, his legacy has two main components in Morrison’s view.

“He’s been so influential in determining what we find funny over 50 years,” she says. “That’s a really large achievement.”

What’s more, Michaels pioneered the idea of a live American comedy showcase in late-night on Saturday and then proceeded to thrive beyond the reach of dozens of corporate overseers.

“He’s built this whole culture with walls around it,” she says. “It’s like a mafia family.” Being the don carries weight with staff but also guest stars, political figures and in his own corporate universe. NBC, during the existence of SNL, has been owned by RCA, General Electric and now Comcast. The clout of Michaels is such that when Comcast CEO Brian Roberts paid a visit after the NBCUniversal transaction, “he had to wait outside Lorne’s office before he was shown in,” Morrison marvels.

“Lorneworld,” as this walled environment is often called, does have its detractors. A number of comedians, critics and figures in media and culture say the downside of the level of control exerted by Michaels is a stifling of voices and, effectively, the perpetuation of a monoculture.

“There’s a segment of the comedy industry that feels he’s the evil master,” Morrison acknowledges, “presiding over a comedy version of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, like a factory … These tend to be the people who are not inside the clubhouse. Lorne does like a club.”

Lorne illuminates the unlikely trajectory of a Toronto-born son of a furrier from Canada to a succession of short-lived and unsatisfying Hollywood gigs to the planets-aligning birth of SNL in 1975. That in itself merits a lasting legacy, Morrison contends, especially given the biblical twists and turns that nearly stopped the cameras from lighting up in 1975. “The fact that it happened is a miracle and a test to Lorne’s unflappability,” Morrison says. “In the very first notebook that I filled, I wrote, ‘This is a man who’s never used an exclamation point.’”