More than 30 years after Austin police found four teenage girls brutally murdered inside a local yogurt shop, HBO is re-examining the case in its upcoming documentary series The Yogurt Shop Murders.

Often described as the case that stripped Austin of its innocence, the tragic 1991 killings sent shockwaves through the community for years as the investigation dragged on. To this day, the affected families seek answers about what truly happened to Amy Ayers, sisters Jennifer Harbison and Sarah Harbison, and Eliza Thomas.

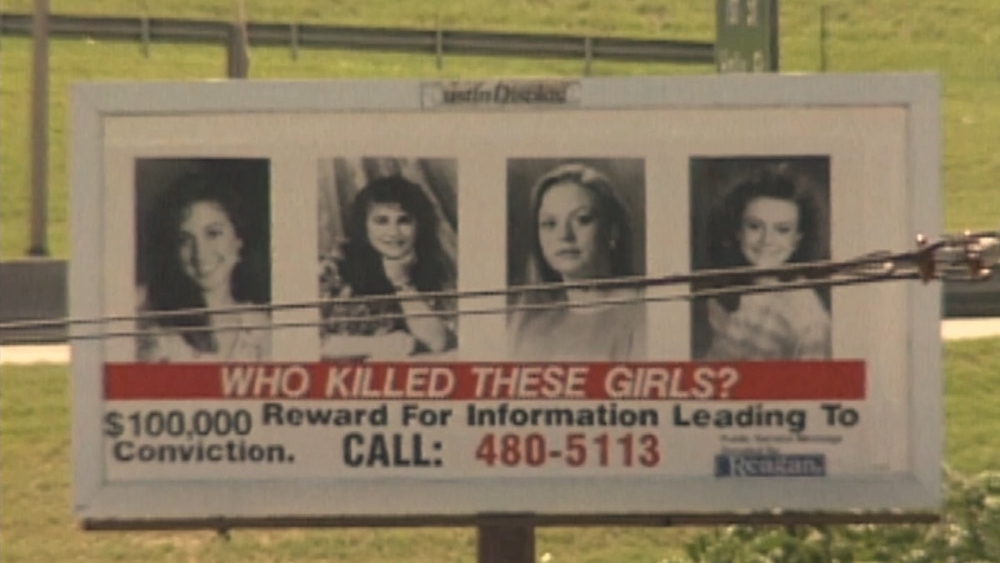

“I was in Austin in the late 90s, and the billboards were up everywhere, and you would go to parties, and people would talk about their theories about what happened,” director Margaret Brown, an Alabama native, tells Deadline.

Through a combination of archival footage and recent interviews with the investigative teams, the victims’ parents and siblings, and the two men who served time for the crime, the series raises important questions about law enforcement practices and the power of public perception as well as offers a poignant observation about the endurance of grief.

In the interview below, Brown speaks more about the project.

DEADLINE: I understand you live in Austin, so what was your understanding of this case before you took on this documentary?

MARGARET BROWN: I was in Austin in the late 90s, and the billboards were up everywhere, and you would go to parties, and people would talk about their theories about what happened. I have a lot of friends who are reporters, and they would all talk about it. My best friend is a reporter, and when I told her I was considering doing this project, she was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s the craziest unsolved crime in Texas, and there’s so many twists and turns…’ In Austin, people talk about it and have for years. I just have this memory of seeing those billboards everywhere and just them being really haunting.

DEADLINE: Once you were on board, how did you start to figure out the best way to tell this story, which as you mentioned is already very infamous?

BROWN: I didn’t want to do the project until I saw the archival footage, because, to me, it’s so much about that time period. Austin was really different. I mean, I wasn’t there then in the early 90s. I was there in the late 90s, [and] it was different enough then. So I really wanted to make sure I had the material to kind of capture that feeling. They sent me what they had, and it was pretty evocative. I immediately felt a transportive kind of feeling to the past. I could hear the music that would go with those images, and even how I would light it. It was such a specific vibe. There was something uncanny about it. Then I met the families, and it really shifted, and I realized I couldn’t go as stylized as I wanted to, because I didn’t want to take away from the emotional connection. I thought if I go too far in that direction, it sort of strips away some of feelings I got when I was just sitting with them. So I still stylized it, but I definitely scaled it back.

DEADLINE: The documentary is sort of telling two stories, because you’re explaining the years-long investigation while also underscoring all of the trauma the families have gone through over the last three decades. How do you find the correct balance there?

BROWN: I mean, I just tried to go in and emotionally respond without judgment as much as I could to whatever the person in front of me was saying. I was really taken by how affected people were by this specific event. Claire Huey, who made the the film that never got finished, she was one of the first people I met. She gave us all that. She gave the production all this footage and and it completely changed her life. She was a filmmaker like me, and she stopped making movies after that, and that was how much the story impacted her. She just couldn’t get her head around it. I think that the power of what happened really hit people. I just tried to go in and listen and not judge.

DEADLINE: Speaking of Claire, we do hear from her in the documentary. What do you think her perspective adds to this story?

BROWN: I mean, I think it’s a parallel to my experience. A lot of times I would watch her footage and I would be like, ‘Oh my God, that’s exactly how I feel. This is so overwhelming.’ It was a really hard series to make, and it was just such a world of darkness. I think like knowing there was someone else who knew what that was like — often, I would just call her to talk about it, because she lives around the corner. Now she’s like a meditation teacher. I’m trying to encourage her to make movies, because I think she’s amazing, and she’s such a empath, and she’s she cares about people so deeply. That’s what made it hard for her, was because she cared so much. I think, also, just being a young filmmaker, she was making it so many years ago, having the confidence to know you can put it all together, because it’s overwhelming story, there’s so many twists and turns, and you end up sort of back where you started a lot of the time when you’re trying to piece it together. I have a whole team helping me. She was a former student. I just can’t even imagine. It would be so hard.

DEADLINE: You go very deeply into the ways that this case has traumatized the families and others involved and, for the most part, avoid any conspiracy theories about what may have happened. What made you take that route? And how did working with these families shape your perception of true crime in general?

BROWN: To be honest, I don’t watch a whole lot of true crime…I didn’t really want to cloud my head by a formula. I did listen to some podcasts, and I was so put off by the tone of most true crime. Not all of them, but most true crime podcasts seemed to forget that these were people.

When you meet the families, I don’t understand how you could. It’s just so painful to sit with people who’ve gone through this. It really takes a toll on you. Maybe it’s because they don’t have to meet the people when they’re making them, they can just listen. People like to feel like they’re figuring out things. I mean, me too. I’m not trying to say that’s not interesting to me, because, of course, it is interesting to try to figure out a puzzle, but in this specific series, I didn’t feel like that. It is impossible, if you meet these people, to make it that way. You feel for them so much.

DEADLINE: There is a very affecting moment in the final episode where they dig up the time capsule for Amy Ayers. How was that for you to witness?

BROWN: Probably how it was for you to watch. I just so felt for the Ayers family and, I mean, we really consolidated that scene. They were trying so hard to find it. We knew it was there. It became like this sort of bonding experience that day, because so many people showed up to help. It was actually really moving how many people just really cared about the Ayers family and them just getting this ode to their daughter up to the surface.

DEADLINE: As you put together this story, what emerged as the most frustrating part of the case for you?

BROWN: What I’m interested in is an exploration of what it means to be a human and go through grief, and how different people grieve. Then there’s this insane story of all these twists and turns and rabbit holes, which the true crime audience is interested in. I’m not as interested in that, but I am interested in it. You need a story to hang your hat on, right? So this film would not exist without that crazy story. There’s multiple threads on my phone with the producers and the editorial department and everyone talking through theories. We were all trying to crack it in some way, or follow a different theory, or follow a different rabbit hole, but it’s balancing that search to solve the crime — which, for me to think I can solve the crime when hundreds of police departments and DNA specialists and all these people are trying to solve this crime, for me to think I can do that is a little hubristic, I think. But of course, we still wanted to. I think, as I made it, what pulled me through the three and a half years of making it was really just sitting with people who I think had a lot of wisdom around pain and living life with pain, which we all have to do. We all suffer. These people have gone through some really f*cking extreme suffering, and I felt like I got a lot out of just listening to these families talk and listening to Claire talk, and listening to some of the investigators who gave their life and ruined their marriages to this case.

DEADLINE: Since the case remains unsolved, the story is still ongoing. How do you find a natural conclusion for the story you are trying to tell?

BROWN: Well, because I was interested in memory and grief… I mean, without again giving a spoiler, there are some things that happen in the fourth episode. I would never call it closure, because the families will never have closure. But there are things that approximate that.