When Manuele Aufiero was a child, his parents took him hiking along reservoirs in northern Italy. But it wasn’t a typical reservoir. This water was constantly drained and replenished, raised by pumps when electricity was cheap. When a nearby city needs electricity, the water is drained from the reservoir and the pump is reversed and turned into a generator.

This technology, known as pumped storage energy storage, or “pumped hydropower” for short, has been around for more than a century. Such facilities are some of the largest “batteries” ever built by humanity. According to the International Energy Agency, 8,500 gigawatt-hours of electricity are stored in pumped hydropower reservoirs around the world.

Pumped hydropower can produce electricity for hours on end, and power plants are becoming increasingly important as intermittent energy sources such as wind and solar become more popular. However, there are only a limited number of places on earth with suitable topography for installing pumped hydropower reservoirs.

“I’m obsessed with pumped storage hydropower,” Aufiello told TechCrunch. “It’s not enough just to keep deploying renewable energy.”

So he decided to solve the problem by moving the technology to sea. He co-founded a startup company, Sizable Energy, to turn his ideas into reality.

Sizable recently raised $8 million in a funding round led by Playground Global with participation from EDEN/IAG, Exa Ventures, Satgana, Unruly Capital, and Verve Ventures, the company exclusively tells TechCrunch.

This startup power plant looks like an hourglass. Sizable’s concept specifies two sealed, flexible reservoirs, one floating on top and one at the bottom of the ocean floor. They are connected by plastic tubes and several turbines.

tech crunch event

san francisco

|

October 27-29, 2025

When electricity is cheap, the turbine pumps ultra-saline water from a lower reservoir to the top. When the grid needs energy, Sizable opens a valve and the water in the reservoir, which is heavier because it contains more salt than the surrounding seawater, falls into the reservoir below. The water flowing through the pipes turns a turbine that acts as a generator.

“From an energy balance perspective, what we’re doing is lifting blocks of salt, but instead of using a crane, we’re melting the salt and pumping it out, just because it’s easier and simpler,” Aufiello said. “Other than that, we’re just lifting a lot of salt.”

By transferring pumped hydroelectric power to the sea, Sizebull aims to mass-produce technologies that are impossible on land.

“Every time you build a pumped storage power plant on land, you have to design a concrete dam for that specific location and adapt the technology there,” Aufiero said. “Building offshore streamlines production, and everything we do is the same regardless of the final deployment site.”

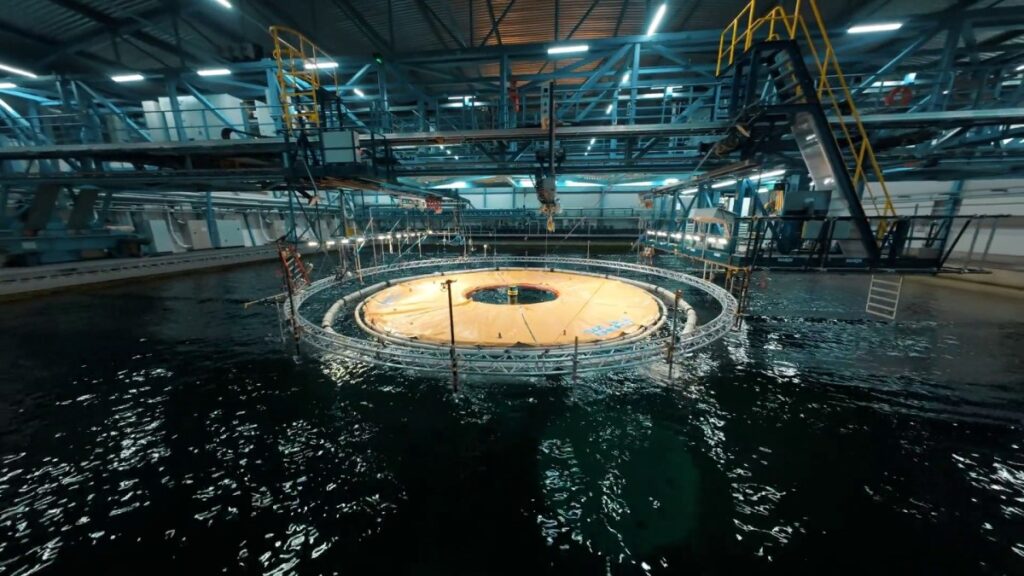

Sizable tested a small model of a wave tank and a reservoir off the coast of Reggio Calabria, Italy. The company is currently testing floating components prior to commissioning a full demonstration plant. By 2026, we hope to have several commercial projects in locations around the world.

At full size, the turbines each produce about 6 to 7 megawatts of power, and there is one for every 100 meters of pipe. Deeper locations have more storage potential, and each commercial site will host multiple reservoirs. Sizable wants to offer energy storage for 20 euros (about $23) per kilowatt-hour, about one-tenth the cost of grid-scale batteries.

The technology would pair well with offshore wind projects, as sharing the electrical connection to land reduces costs. But Aufiero said Cysable’s reservoir could potentially connect to any power grid near bodies of water at least 500 meters (1,640 feet) deep.

“We believe that long-term energy storage is necessary not only for the integration of renewable energy, but also for increasing the resilience of the power grid,” he said. “Traditional pumped storage hydropower and batteries can’t keep up with this. We need something new.”